Lent 3 C,

Year C

Isaiah 55:1-9; 1 Corinthians 10:1-13; Luke 13:1-9

Luke

13:1-9

Repent

or Perish

13 1At that very time[1]

there were some present who told him about the Galileans whose blood Pilate had

mingled with their sacrifices.[2]

2 He asked them, “Do you think that because these Galileans suffered[3]

in this way they were worse sinners[4]

than all other Galileans?[5]

13 1At that very time[1]

there were some present who told him about the Galileans whose blood Pilate had

mingled with their sacrifices.[2]

2 He asked them, “Do you think that because these Galileans suffered[3]

in this way they were worse sinners[4]

than all other Galileans?[5]

3 No, I tell you; but unless you repent,[6] you

will all perish as they did.

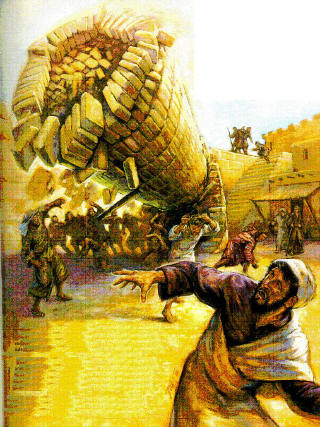

4 Or those eighteen who were killed when the tower of Siloam

fell on them—do you think that they were worse offenders[7] than

all the others living in Jerusalem

The

Parable of the Barren Fig Tree

6 Then he told this parable: “A

man had a fig tree[9] planted in his vineyard;

and he came looking for fruit on it and found none. 7 So he said to

the gardener, ‘See here! For three years I have come looking for fruit on this

fig tree, and still I find none. Cut it down![10] Why should it be wasting

the soil?’

8 He replied, ‘Sir, let it

alone for one more year, until I dig around it and put manure on it. 9 If

it bears fruit next year,[11] well and good; but if not,

you can cut it down.’”[12]

As usual, our Gospel reading

for this week, Luke 13:1-9, lifts up some very difficult theological issues.

But that’s why we preach, isn’t it? That’s why preaching is important. If the

ideas were easy, they wouldn’t hire people like you and me to untangle the knots

and make sense out of them. J

This week I will only talk about the first half of the Gospel reading. For one thing, the first part, about death and sin and repentance, raises some powerful issues in and of itself, and probably, originally had nothing to do with the second half, about the survival of a fig tree. For another, I'm lazy and spent all week on the first half and will have to wrestle with fig trees another time.

According to the narrative

arc that Luke is following or creating, this is the very last part of a much

longer “speech” (or loose collection of sayings), that Jesus delivers after

dinner at the home of a Pharisee. It was evidently a fairly large gathering because

there were a number of people from the town present. The total speech runs from

Chapter 12:1 to 13:9 and covers a number of topics roughly woven together (some

more smoothly than others) around a larger theme about being vigilant in the

face of crisis. Some of the issues included keeping their faith, and remaining

morally and ethically strong, even under difficult conditions.

For example, the speech

contains the statement that we shouldn’t spend our lives worrying about what we

should wear or eat. So, Jesus says, “Remember the lilies of the fields: they

neither toil nor spin, yet even Solomon in all his glory was not arraigned like

one of these” (12:27). On another, he says to not give up on your faithfulness

just because times are hard. And there's the story of the servants waiting for their

master to come home after his wedding, who eventually got tired waiting and gave up on

him. Jesus says, “blessed are those [servants] whom the master finds when he comes”

(12:37).

Finally, here in 13:1-9, he comes to

something of a climax in his talk. It is a call to repent and change our ways,

a “change of heart and life manifest in fruitful lives” (New Interpreters' Study Bible). As I mention in the notes on the text above, Luke mentions repentance more often than any

other book in the Bible. In fact, close to more often than all of the rest of

the New Testament combined.

Then, that evening, presumably

after dinner, someone in the crowd raises a question about a recent tragedy concerning

some grizzly deaths that had occurred in the temple. Evidently Pilate had punished

some Galileans for an unspecified crime (likely their involvement in an

insurrection plot) by killing them and sprinkling their blood in with the blood

of the sacrifice on the Temple altar. Incidentally, we have no other record of this

happening, however it is very much in keeping with the gruesome policies of Pilate.

Jesus’ response to it indicates that the questioner was probably suggesting

that God had caused the deaths as a punishment for their being “worse sinners” than

others.

Background “Riffs”

As an aside, here are a couple

of “riffs” that you could go off on in your sermon that could flesh out the

background of this simple two-sentence story. First would be to think about the possible underlying emotions driving this question. For example it could have reflected a

basic prejudice by those in Jerusalem against the lower class Galileans who they believed should be considered sinners, prima facie, solely because of their

class. An attitude that still lies just under the surface in much of our

discourse about race and nationality and gender today. Or you might mention a

frequent attitude among marginalized peoples that any opposition to the

government is out of line and sinful. “Those

people,” they might say, “could have put the lives of the rest of us in jeopardy by that

action; they should have just stayed in their place and not tried a protest.” But

in either case, the first thing Jesus says is no. I’ll come back to the second

half of Jesus’ response in a moment.

A second riff could be to give

a little primer on sacrifice as the mode of worship in the first century. It

may have been more bloody than our modern methods of worship, but no less

significant. In ancient Israel, sacrifices were gifts to God as a thank

offering for the bounty that God had given them. And they saw it as a

transformation of something temporal (the animal) into something transcendent

(the smoke, the spirit from the animal). [13] We retain a lot of the symbolism

of sacrifice in our worship today, but without the (bloody) physical actions behind them. It’s not our

21st century mode of worship, but don’t let the bloody aspects of it derail us

from looking at Pilate’s even more bloody response and the moral and

theological issues that the story raises.

|

| Traditional location of the "Pool of Siloam" |

The second story raised that

evening came from Jesus himself. It was about a time when a tower in Siloam[14] by the waters fell over on

top of people and killed 18 of them. This was probably tower that guarded the aqueduct bringing

water to the pool of Siloam, that formed part of the old wall of Jerusalem.[15]

It was a terrible tragedy. Greg

Jenks, a New Testament scholar at St Francis Theological College, in Australia,

believes that both of these stories may be related. At about the same time that

Jesus was making his way to Jerusalem, Pilate began an aqueduct project to

bring more water to the city. That’s a good thing, but he was going to pay for

it by stealing money from the Temple treasury and many local Jews protested that. So, the first group who died could

have been enraged Jews who protested against the robbery, and then paid for it with their

lives. And the second group could have been the workers on one of the towers related

to the water project.[16] So, Jesus asks, were they suggesting that the

people who Pilate killed and had their blood mixed with the Temple sacrifices were worse “sinners”? And that those who died in the tower collapse worse “offenders”

for what they had done?

He asks both of these

questions in a rhetorical way, The implication in both was yes, that is exactly

what they were suggesting. Yes, they believed that because these poor people died

the worst possible deaths, therefore they must have been the worst possible

sinners.

The first part of his

response to both questions is simple, of course not. And that answer is very helpful.

God is not a killer. Thinking so is nice when you are talking about a Saddam Hussein or

Bashar al Assad (brutal dictator of Syria) dying, but the argument gets a

little weak when you’re talking about hundreds of thousands of innocent people

in Haiti during its earthquakes and floods and cholera epidemic (which was, by the way, introduced to the island by the United Nations earthquake relief workers). Did they sin more than

us, and therefore God destroyed their country? Of course not, and Jesus makes

that plain.

But the second part is more

difficult. I can understand his saying that you need to have a life of

repentance and new meaningfulness, but it at least sounds like he is adding that if you don’t repent you will die just

like those Galileans did, or you’ll die the way

that they did. It’s the “like they did” part that remains troubling.

I don’t think he means that if you are a sinner, you

will die in the same manner that they

did. That is, you’ll have your blood mingled with some kind of Jewish

blood-offering in a temple. And I don’t think he means that if you don’t

repent, you’re going to die too. That one doesn’t actually make any sense,

because of course you’re going to

die. Everyone dies. It’s the end of life. It comes. Get over it. It doesn’t

mean you’re a sinner if you die. It means you are mortal and your clock ran

out.

But surely he does mean that if you don’t repent then

you will die in some way that is similar to those guys. And that’s your biggest

take home for a sermon from this passage. If you die and you have not turned

your life around (Greek: metanoia)

then it could, in fact, be argued that you will die cut off from God and from hope

and peace in your bones, the very way that these people (might have) died. I

say “might have” because since none of them lived to do interviews about their spiritual

life we have to just say, “for the sake of argument, let’s say that none of

them had a meaningful connection with God, and if you don’t turn you lives

around, then you will die with the same lack of meaning." Jesus is not saying

that that unless you repent (turn your life around) you’ll die too, just like

they did, because you certainly will

eventually die like they did, no matter what your repentance status is. But he

is saying that when you die it will be a cut-off, soul-evacuated life—like theirs

(probably) was.

One thing that might be helpful is to point out that, while the literal meaning of the word "perish" (apóllymi), refers to dying or eternal punishment, in the New Testament it is also often used to mean something closer to being lost or estranged or separated. For example, Mark 8:35: "those who want to save their life will lose (apolesei) it, and those who lose their life for my sake, and for the sake of the gospel, will save it." Or the three parables of Jesus in Luke 15, the shepherd who lost a sheep, the woman who lost a coin, and the father who lost his son, all use the word, apóllymi for the thing that is lost, and clearly none of the stories are about someone who is being punished for eternity for their sins.[17]

A more nuanced (and more accurate) reading of Jesus' words here about how we should respond to the deaths of the workers and protesters is to separate the two clauses. On the one hand, no, those people did not die for their sins. And on the other hand, you should not die separated from God. They are not closely related thoughts. You should turn your life around in meaningful, God-related, way now, because you may die estranged, alienated, separated from the love of God and others and yourself.

One thing that might be helpful is to point out that, while the literal meaning of the word "perish" (apóllymi), refers to dying or eternal punishment, in the New Testament it is also often used to mean something closer to being lost or estranged or separated. For example, Mark 8:35: "those who want to save their life will lose (apolesei) it, and those who lose their life for my sake, and for the sake of the gospel, will save it." Or the three parables of Jesus in Luke 15, the shepherd who lost a sheep, the woman who lost a coin, and the father who lost his son, all use the word, apóllymi for the thing that is lost, and clearly none of the stories are about someone who is being punished for eternity for their sins.[17]

A more nuanced (and more accurate) reading of Jesus' words here about how we should respond to the deaths of the workers and protesters is to separate the two clauses. On the one hand, no, those people did not die for their sins. And on the other hand, you should not die separated from God. They are not closely related thoughts. You should turn your life around in meaningful, God-related, way now, because you may die estranged, alienated, separated from the love of God and others and yourself.

There are two things going on here.

The first, I think, is the

deeper meaning that you shouldn’t throw blame around when you see suffering.

That’s not only rude and in poor taste, it’s also a wrong use of the event.

Instead use it as an occasion to change your own life.

When you see a car accident,

don’t say, “whew! Those stupid bozos. I’m sure glad I’m not like those guys.” A

better response would be to feel shaken and torn inside and think to yourself, “how

awful that was. It makes me realize how fragile and temporary life is. I should

take life more seriously and meaningfully.” The most important “learning” that we

should find in a death (if indeed there is one, and sometimes I’m not sure), is

not that the person who died deserved

to die, or that God “Took him home.”

It’s silly and unproductive to think that God picks and chooses who to kill off

according to the level of sinfulness in the deceased, or from some dark divine

plan that only God understands.

When I preach on this story,

I often use a real story of an exchange I heard at the collation following a

funeral years ago. A lot of well-intentioned people were milling around saying

it was sad, and all, that old John died, but y’know, he was a rounder back when

he was a kid, and God probably gave him that diabetes and gangrene that took

him, as a punishment for all that.” After two or three of these exchanges, an

old Methodist on-the-wagon alcoholic, who knew a thing or two about “rounders”

and sin, glowered at them over the punch bowl and said, that if God strikes

down people for the sins of their youth, then every single man and woman in

this town would be walking around with a limp.”

I love that story. As Paul

says, “All have sinned and fallen short of the glory of God” (Romans 3:23).

Whenever we blame someone’s death on their sin, or on God’s capricious taking

them home, or because it was “their time,” we tread in dangerous, almost evil

waters.

There are only two potentially “good” responses to death

(note the cautionary use of quotes and italics, because any good response can

be abused if we try hard enough). One would be to ask how can I turn my life around and become a better

person in light of the death of this loved one? Or “How can I celebrate this

person’s life by creating a better life?” The second is like it. “How can I

create a world in which there is a smaller number of children washing up on the

shores of Greece or Spain or Britain, or emergency rooms or jails or homeless

shelters in the US?”

So, it’s most likely that when Jesus says that without repentance, you

will die as they did, he was saying something like, “unless you repent and turn

your life around you will die—not in the manner

they did, but in the spiritual state

that they did. That is, not that repentance will keep you from dying at all (which

it clearly will not), or that repentance will keep you from dying with a tower

falling on your head (which would be interesting but silly for the story), but from dying while lost, alienated,

and separated from God. Unless you change and return to God, you will die cut

off from God as (presumably) those people did. So, repentance is not related to

their death, it’s related to their life. Their sin (of separation) had nothing

to do with their deaths. It had to do with their lives.

Conclusion, summary and difficult issues

Someone in the crowd raised this

issue because he or she believed that there was a direct correlation between

sin and suffering. These people suffered horrible deaths. Does that mean that

they must have been terrible people? It is the question found in Job, Psalm 37

and 73 and others. John 9:2. “Rabbi, who sinned, this man or his parents that

he was born blind?”

We (you and me) occasionally

raise that question too. And occasionally there appears to be a link between the two. But on the whole, hunting

down that link is a bad direction to go in. The clarity of the down side is far

worse than the ambiguity of the up side. If we say that God punishes those who

are sinners and rewards those who are saints, then we get dangerously close to

saying that the people who died in the 9-11 tragedy (or in the plane crash in Ethiopia, or the racist mass killing in New Zealand...or whatever) were somehow more guilty than the rest of

us. And if we say that God rewards those who are good, then we slide overly

close to saying that some people are financially successful

because they were somehow more morally good than the rest of us. I don’t know

about you, but I’m not prepared to say that. How about Martin Shkreli, the hedge

fund manager, who bought up the rights to Daraprim, an important and inexpensive

life-saving drug, and then jacked up the price 5,000 percent, actually putting

at risk the lives of thousands of people? And who had absolutely no remorse for his actions later when questioned about it in Congress.

Jesus brushes aside that

theology and recasts the issue: If you don’t change your ways, and live a life

of repentance and trust in God, then you are going to approach death with a

life that has no meaningful connections to life eternal, a meaningless life.

Without a life of repentance, all of the rest of life is empty and lost. I

think that’s a more fruitful direction in which to go, and I think it was what

Jesus was getting at: don’t dwell on whether God did this awful act; dwell on

pondering what we are going to be like in light of it? Who am I going to be in light of it? How is it

going to change me?

Occasionally we see people

who are wonderful people and successful and healthy and we can think we see a

direct relation between their moral life and their checkbook or health. And

occasionally we’ll see a real scumbag who died young or badly with some degree

of justice. However, we all can also remember examples of truly decent people

who died long, protracted, awful, unjust deaths. So don’t ascribe the hand of

God in those. It just isn’t there. What Jesus calls us to is the quality of life, the relation with God life. Not a

financially or medically rewarding life. Don’t ask a theological question about

the ethics or morals of people who died in an accident, ask how that accident

can bring us to change our relationship with God and with our world. This is

the theological question that makes the most sense. You all are going to die

anyway, just like the people whose blood Pilate mingled with the blood at the

altar and who died under the crushing collapsing building. You don’t have a

choice in that. But you do have a choice in how you live your life before you

get there.

[1] “At

that very time” (en autōi tōi kairōi).

A frequent idiom of Luke’s. Emphatic about the particular time: “At that very time “at the time itself.” The kjv has “at that season.” There have

been a number of guesses as to what “time” he was referring to, but there’s no

consensus on them. Fitzmyer says that while “The transition creates the

impression of a report about something that has recently happened,” it may just be “a transition composed by

Luke to join this episode to the foregoing.

(Joseph A. Fitzmyer S.J., The

Gospel according to Luke X–XXIV: Introduction, Translation, and Notes, vol.

28A, Anchor Yale Bible [New Haven; London: Yale University Press, 2008], p.

1006.

[2] “Whose

blood Pilate had mingled with their sacrifices” (hoôn to haima Peilatos emixen meta toôn thusioôn autoôn). The verb emixen is first aorist

active (not past perfect) of mignumi, a common verb. The net and

niv have “mixed.”

[3] “Suffered” (peponthasin). Second perfect active indicative third

plural from paschoô, common verb, to experience, suffer. The

tense notes that it is “an irrevocable fact” (F.F. Bruce).

[4] “Sinners” (“öåéëÝôáé). From QìáñôÜíù, hamartanō (to miss the mark [and so not

share in the prize]), i.e., sinful, missing where we should be in terms of righteousness.

[5] “Worse

Sinners than all other…” (hamartoôloi para pantas). Para means “beside,” as in being placed beside the Galileans

for comparison, and so beyond or above (with the accusative). Lit. they sinned beyond all the Galileans.

[6]“Unless you repent” (ean meô metanoeôte,ìåôáíïyôå). Have a change of heart, change one’s ways. Lit.: Unless you reform your lives and the way you

live…. Present active subjunctive of metanoeoô, to change both one’s mind and conduct, and

keep on changing. Calls to repent are much more common in Luke than in other NT

writers.

[7] “Offenders”

(öåéëÝôáé, opheiletai). Literally, debtors, not sinners as in v. 2, and as

the kjv has. See 7:41; 11:4;

Matthew 6:12; 18:24-34. One

who is under obligation, One who owes

something to another. That is, a person indebted, a debtor. Translated as

sinner, or offender, because debtors were considered transgressors of the law

by virtue of their not paying their debts. From “öåßëù, “öåéëÝù, opheiloô opheileoô, to

owe (pecuniarily); figuratively to be under obligation (ought, must, should);

morally to fail in duty.

[8] “Unless

you repent” (ean meô metanoeôseôte). First aorist active subjunctive, immediate repentance

in contrast to continued repentance, metanoeôte in verse 3, though Westcott and Hort put metanoeôte in the margin here. The interpretation of

accidents is a difficult matter, but the moral pointed out by Jesus is obvious.

Again, calls to repentance are mentioned more often in Luke than in any other

gospel.

[9] “Fig tree” Fig trees in the

Hebrew scripture were often symbols for Judah or Israel. Cf. Hos 9:10; Micah

7:1; Jer. 8:13; 24:1-10).

[10] “Cut it down!” ἔκκοψον

[οὖν] {C} “In order to reflect

the balance of external evidence for and against the inclusion of οὖν, as well as the absence

of any compelling consideration relating to transcriptional and intrinsic

probabilities, the Committee felt obliged to retain the word in the text, but

to enclose it within square brackets, indicating a measure of doubt that it has

a right to stand there.” Metzger, Textual Commentary on the Greek New

Testament, second edition.

[11] “If it bears fruit next year” (kan men poieôseôi

karpon eis to mellon). Aposiopesis,

sudden breaking off for effect (Robertson, Grammar,

p. 1203). See it also in Mark 11:32; Acts 23:9. Trench (Parables) tells a story

like this of intercession for the fig tree for one year more.

䨁

[12] “At the end of this verse there is added in some manuscripts, ‘as

he said this, he called out, ‘Let the one who has ears to hear take heed.’”

(Fitzmyer, p. 1009).

[13]

See for background, William K. Gildershttp, “Sacrifice in Ancient Israel” www.bibleodyssey.org/en/passages/related-articles/sacrifice-in-ancient-israel.aspx.

Retrieved, 02/27/16

[14]

See “The Locations of the Pools of Siloam,” https://againstjebelallawz.wordpress.com/2011/04/28/the-locations-of-the-pools-of-siloam/

[15] Fitzmyer, p. 1008.

[16]

His thoughts on this, and extensive quotes from Josephus’ writings about Pilate’

brutality on the Jews, can be found here: http://gregoryjenks.com/2013/02/24/lent-3c-3-march-20143/.

[17] Gerhard Kittel, Gerhard Friedrich, and Geoffrey William Bromiley, Theological Dictionary of the New Testament (Grand Rapids, MI: W.B. Eerdmans, 1985), p. 67.

[17] Gerhard Kittel, Gerhard Friedrich, and Geoffrey William Bromiley, Theological Dictionary of the New Testament (Grand Rapids, MI: W.B. Eerdmans, 1985), p. 67.