If You Lived Here You'd be Home by Now

Life and Grace and a Journey Home

Better (Not) Call Saul

The Bible and Mike Johnson

Why do Some People Not Report Abuse?

The recent news about E. Jean Carroll and all of the swirls of conversation around it about why she (and others) waited so long to call out her abuser, reminded me of a famous Gospel passage, Matthew 25:14-30. It's the story normally referred to as the "Parable of the Talents." Hang in with me. It's not as boring as you think.

Two of the three managers keep quiet and go along with the program and are rewarded later with more power and money. But one of them denounces the system as a scam, accusing the boss of taking in more income from borrowers than he was owed and in some instances stealing from investments he didn't even make. So he refuses to go along. He holds onto the small amount of money he got from the investor and then gives it back to him unchanged, probably so that he will not be accused of being a participant in the crime.

The powerful boss responds to his being stood up to by the lowly manager with a punishment that is swift and deep. His remaining money is taken from him and given to those who kept silent, and he is sent into outer darkness. And no one comes to his defense. The other managers don't say a word. There's no HR to go to. There is no court that would believe him, or probably even hear his case.

So, here's a thought, does what happened to him say anything about why it is that so many women decide to suck it up and remain silent even when their boss is an asshole and sexual predator?

Just wondering...

Stan

It Was the Building that Saved Him

Stan G. Duncan

Periodically his wife would come in and plead with him to get up and do something to get his life going

again. He wouldn’t move. He could no longer work, so for him, he lost not only his job but also his manhood. He was no longer a good provider, so what good was he? Nothing, he thought, so he just drank beer, clicked channels, and avoided letting his mind function.

He said that now and then he’d say a few words to his wife during dinner, or at night, but more or less he let his life slide into a deep pit that he couldn’t get out of. One day, some years after the accident happened, he remembered vaguely that his wife packed up some things and said goodbye. He absently wondered what she was up to but didn’t think about it. Then that evening he listened and looked around and realized that she was gone. She was really gone. Her things were gone. A note was left. She wouldn’t be back. She wrote she had tried to help him, to talk to him, to love him, but he wouldn’t let her. She had failed. She mourned, she cried, she prayed, but she couldn’t stay.

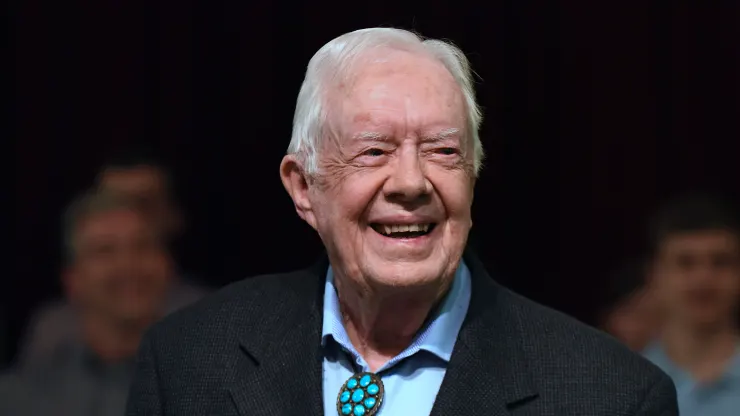

For a while, he responded simply by falling deeper into his despair. Aside from eating and sleeping, which he did poorly and sporadically, he barely moved. Just sat in his chair drinking and clicking. Then one day he saw Jimmy Carter on TV. It’s been some time now, but he recalled that Jimmy was in Philadelphia rehabbing old houses. It was a special day, a “disabled-working-on-the-houses” day. All the people in the work crew had lost hands or feet or were otherwise crippled up bent over, or in wheelchairs. He saw this crowd and distantly saw himself. Here were people worse off than he was and they were building houses for Jesus.

He pulled himself up from his chair, took a shower, packed some food, crawled into his old camper, and took off for Plains Georgia, to Jimmy Carter’s house. Not a thought as to whether he could actually walk into the home of a former president, he just drove.

Two days later he drove up to the Carter house, and sure enough, there were official-looking people in front, but far from keeping him out, they invited him in. He just walked up to the door, knocked, and a moment later Rosalyn Carter came to the door. He stumbled and stammered and told her his story and she said just a minute. And then President Carter appeared. In a bathrobe, holding a cup of coffee. He invited George in. The three of them sat at the Carter breakfast table and talked for over an hour. George told his story, and they listened. They prayed together, shared scripture together, and then in the end Jimmy got on the phone and called some people he knew who planned projects for Habitat to see what they could do to set George up with a work project sometime soon.

And there he was across from me by the punch bowl telling me his story. I was moved, I was humbled. It was a great story. “It was the work what saved me,” I remember him saying. “When I was rebuilding them houses, I was actually rebuilding my life. If I hadn’t started working for Jesus, I would’ve died.”

The Gift of Goodbye

It's an adventure and it's exciting, but it's also poignant and just a little bit scary. Sometimes it goes well and sometimes it doesn't, but if you could measure the level of emotion in the air for these days, it would be deep into the red zone.

There is a ritual in Boston and many other places that takes place every year around the end of May and the first of June. That's when literally thousands of college students dump all of their collected dorm and apartment paraphernalia into the streets to be picked up and sold or given away. Desks, chairs, beds, lamps, whatever. Boston is a huge college town, so this act is a bonanza for area homeless shelters and thrift shops.

There is a different, but related, ritual that is happening right now. It is the ritual of an equally large number of cars with weepy parents and anxious 18-year-olds driving down Francis Ave. in Cambridge, or Commonwealth in Boston, or wherever, and letting go of someone they have known and lived with, literally all of his or her entire life. It's an adventure and it's exciting, but it's also poignant and just a little bit scary. Sometimes it goes well and sometimes it doesn't, but if you could measure the level of emotion in the air for these days, it would be deep into the red zone.

I remember doing this with my kids back in their days. Actually, Kevin and Stanley, the two oldest, were not as big a leap. They both went to the University of Oklahoma, which was only about 15 miles away from where I lived at the time, and I was able to see them now and then for a lot of their time there. With Kevin, it was even less of a break, because, out of a freakish coincidence, I happened to be at OU working on a master’s in economics at the exact time that he was there working on a BA in economics, so we actually passed each other on campus on occasion (a little discomforting, by the way, but don't tell Kevin).

I think my biggest dip into the red zone of separation emotion was when Karla left. She went off to a little private university in Memphis, Tennessee, that specialized in languages and foreign relations, and then after that she traveled the world, even working for a while for the French government. We went for about three years without seeing her. Those were tough times.

Of course, I didn't know all of that on that day when she was bundling up her life and squeezing it into a car to drive off for orientation, but inside I still sensed that a huge break was taking place.

Last week, I happened to be in front of Rockefeller Hall at Harvard (where I once did time myself) and I saw a dozen or so cars come and go with parents dropping off their offspring. Usually, the son or daughter was cool about it -- for kids, excitement tends to swallow up fear in the beginning -- but the mother was visibly emotional. The father, however, remained stoic. He's the guy, after all, and can't show emotions because it's not a guy thing. But after their little girl was dutifully set up in her room and they were alone in the parking lot, the husband grabbed his wife's hand and held it long and tight. I suppose it seemed right to be strong in front of the daughter, but when they were alone, he needed strength.

When I saw Karla for the last time, I didn't do a very good job at that stoic thing either. I think my voice was relatively calm, but my eyes were watery, and they gave me away. She was sweet about it. She didn't make a comment about it, but just gave me a kiss and told me that she'd miss me and would see me again soon. And then the future of the entire world as we knew it suddenly changed forever. And it has never changed back, and it never will.

I remember when I made that big break. I put all of my clothes and books and bedding -- and a banjo -- into a tiny Volkswagen "Beetle" and drove thousands of miles to Vanderbilt University in Nashville, Tennessee, and I did it while my parents were at work, because I was young and stupid and didn't realize that they would want to be a part of the ritual. We had dinner that night and I chatted about everyday affairs as though nothing was changing. And then after dinner I gathered up the last of my things and drove all night long to my new home. It never occurred to me at the time that my excitement was their loss. I can only imagine now, decades later, that they probably would have wanted to stand there on the driveway for a long while after I left, holding hands and dabbing their eyes at the rupture that had just changed their lives as parents.

They are both gone now and looking back I wish I had given them a better goodbye. And one of these days Karla and Stanley and Kevin are all going to be sending off their own "babies" with a similar mix of sadness and sorrow and excitement and thrill. It's the cycle of life and it will never change, no matter why they are leaving or how far they go. Eighteen years are far too few to have in your life someone you love with all of your being and might, but to hold on to them would be worse. Holding close, then letting go; holding close, letting go. Again and again. It happens to those who have kids and even those who do not. It's universal. It breaks you and it heals you. It is what moves life forward whether you want it to or not, and if you allow it, it keeps you from becoming stagnant. It's sad and it's painful, but it is also energizing and creating. It's one of the things that helps us learn what it means to be alive.

Posted 24th September 2002 by Stan G Duncan

Interview with Stan Duncan, author of new book,

THE FIRE ON POTEAU MOUNTAIN

Available now from Amazon.com or Adelaide Books

February 9, 2021

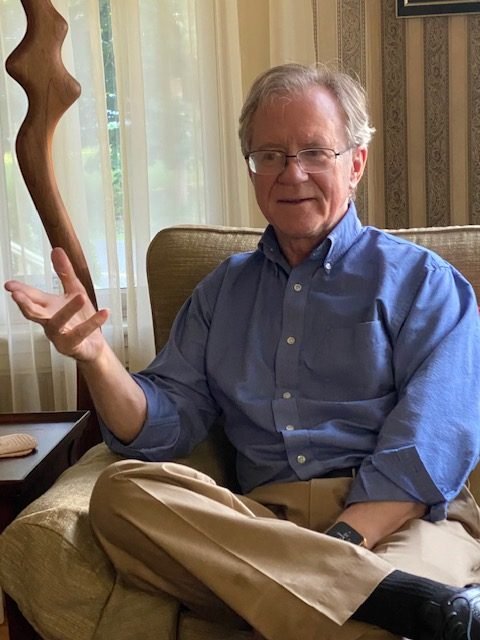

1.Tell us a bit about yourself – something that we will not find in the official author’s bio?

I don’t totally recall what was in the official bio, so some of this will overlap. I am originally from Oklahoma and lived for some years in the small town up in the Kiamichi Mountains where these stories took place. I have an embarrassing number of degrees, two in religion and two in economics and a fellowship at Harvard in both. And I have worked and published in both fields all my life. I was a college professor for a while and a church pastor for a while and a wide variety of other jobs, like van driver, restaurant owner, club pianist, and economics commentator for public radio’s “MarketPlace.” Perhaps my most daring job was in El Salvador, in the late 1980s, where I work as an economic development advisor for a consortium of nonprofits in Central America during the region’s many civil wars. It was the most exciting and dangerous period of my life, and is the setting for my current novel.

2. Do you remember what was your first story (article, essay, or poem) about and when did you write it?

The earliest completed story that I can remember writing was for a creative writing class in my Freshman year of college. It was a series of letters from a young woman off on her own trying to assure her worried parents that she was fine. Each letter creates an increasingly large (and false) world of many friends and a wonderful boyfriend. But when the family evidently (in an unseen letter) has offered to come see her, her notes begin to change. They start encouraging them to not come, and when the family doesn’t seem convinced, they say that one-by-one her friends and boyfriend have either moved away or died and she is now very sad, and that now if they still want to come and visit, they can.

It was overly obvious and a bit “too clever,” but I was trying to build on a theme that a lie can go awry and have consequences, and I was eighteen and it was the best I could come up with. At eighteen, I thought everything I wrote was great.

3. What is the title of your latest book and what inspired it?

It’s called The Fire on Poteau Mountain, which is from the title of the last story in the collection. It was written like a memoir of memories and stories of an aging pastor who once served a small church in a small town called Heavener, Oklahoma. Each story is more or less a stand-alone piece, but the setting and many of the characters interlock. I initially started writing it to put down some of my own memories of that beautiful little place, but the setting and characters soon took on a life all their own, and a collection of short stories (all fiction) began to emerge. Over many years, when I would occasionally run across a difficult conflict or complicated person, or some interesting human interaction, I would wonder how that person or event might be “spun out” into a longer story with new twists and turns, and then eventually it became a book-length collection..

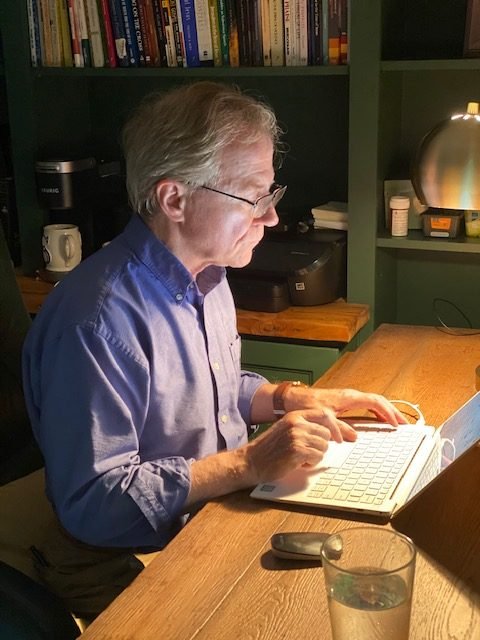

4. How long did it take you to write your latest work and how fast do you write (how many words daily)?

I don’t write fast at all. The Fire on Poteau Mountain was collected over about ten years. A few years ago I published a book on economic globalization, about the ways that problems and issues of trade and finance harm poor people around the world, and that also took about ten years. I hope that’s not the pattern for the rest of my writing life; I’m hopeful that this next one will break that pattern.

I don’t have a real sense of how many words per day that I can put out. It’s been several months since I wrote on a daily basis. Since then life has been filled with retirement, a major move, COVID-19, and chasing love. Some things demand priority even when I don’t want them to.

5. Do you have any unusual writing habits?

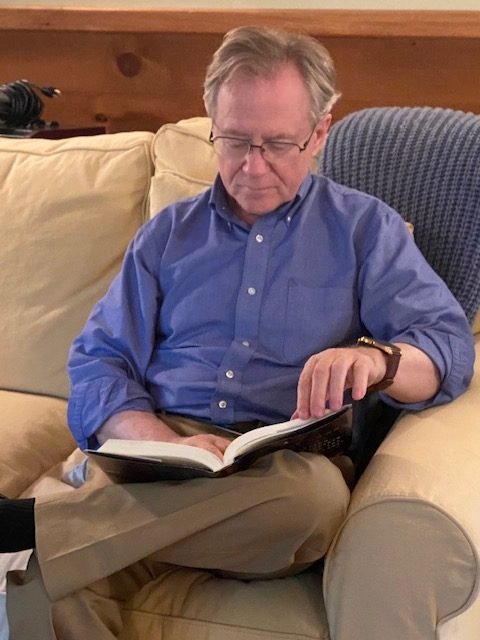

Probably not. For many years my most consistent time of writing was in the early evening after work, when I would settle into the couch, turn on some music, pour a glass of wine, and then write. I’m retired now, so I’m hopeful that after the dust of the new life settles, I can recreate that habit (but with much more time for sitting and writing).

6. Is writing the only form of artistic expression that you utilize, or is there more to your creativity than just writing?

No. My biggest creative expression today is playing and composing music for the piano. I have boxes and boxes of my (largely unpublished) sheet music for bands or choirs or solo piano. I also do pen and ink drawings that have sometimes turned out well. In the past I did some nice wood carving and clay molding and wire sculpting, but it’s been a long time.

I also think I’m pretty good at playing the spoons, but so far I haven’t seemed to have been able to develop much of a fan base for that particular gift. (Maybe someday…)

7. Authors and books that have influenced your writings?

There are so many that it is hard to choose, but here are a few great writers who have fed and inspired me. John Steinbook, Norman Maclean, Pat Conroy, Andre Dubus II, Margaret Atwood, Toni Morrison, Gabriel García Márquez, Ralph Ellison, Ian McEwan, Annie Dillard, Anthony Doerr, Eudora Welty, Walker Percy, and several others I can’t think of right now.

8. What are you working on right now? Anything new cooking in the wordsmith’s kitchen?

The book I am working on now is set during the eighties in El Salvador, where I once lived and worked and loved and nearly died. And it is inspired by those experiences. The tentative title right now is Zacamil, the name of a neighborhood in the capital city, San Salvador, which was a center of political organizing during the war. My protagonist is an economics professor from the US who moves there after his wife died to do research on economic development projects. While there, in addition to encountering the politics and violence of the war, he also meets and has a relationship with a widow and her two children, who live in the Zacamil neighborhood. That area was bombed and strafed and nearly leveled by the government for over a week in November, 1989, resulting in over eight hundred people being killed. And it is the setting for the final conflict and climax of the novel.

9. Did you ever think about the profile of your readers? What do you think – who reads and who should read your books?

This is very hard to say, but it is something I’ve tried to understand many times. Most of my writing before now has been in religion, economics, and human rights, so my reading audience

will probably be at least slightly different. I am hopeful that they will be people who are versed in, or appreciative of, southern literary (slightly Gothic) fiction. That is a genre that I appreciate and live in, and hopefully have written in. My stories are filled with wife-beaters and addicts and molesters, and heroes. Even the good are flawed and some of the villains want to be free of their demons. I think people who have been wounded and discredited, and loved and forgiven will find a voice in these stories. I know that I have, and I’m one of those people.

10. Do you have any advice for new writers/authors?

- Don’t ever give up. And don’t put it off (we all are going to die, and your best seller may die with you, if you don’t watch out).

- Don’t pronounce or preach or proclaim on social or political issues. If you want/need to express them, let it come out of the depths of the story line or the passions and experiences of the character.

- Don’t try to sound overly grand or poetic. Let the dialog sound human and engaged and real. False-sounding dialog kills a good scene.

- Avoid cliches or common expressions. They are fine in your own conversation, but they can mortally wound dialog in a work of fiction. If you must use one, put it in quotes, or have your character say, “well, as the saying goes” or “as they used to say….”

- Strive for authentic renderings of humanity. A weak story line can still be a successful book if the reader identifies with and falls in love with, the heart and hurts of the protagonist.

- There are many more, but I’m a retired pastor, economist and van driver, so what do I know?

11. What is the best advice (about writing) you have ever heard?

Ann Lamott wrote a book some years ago called Bird by Bird, on how to write. I never read it, but I heard her give a talk on it one time and she told the story of its title. When she was young and couldn’t get her mind around how to write a term paper about birds because there were too many of them and she didn’t know how to start. So she went to her father for some advice, and he said to simply take it “Bird by bird.” Perfect. My best advice. Step by step. Move forward. Much of what you will write will be bad. But you’ll never get to the good stuff unless you plow along, putting one bird in front of the other.

12. How many books do you read annually and what are you reading now? What is your favorite literary genre?

A few years ago, when I was on a more regular reading schedule (which is to say, when I was married), I would probably read about fifteen to twenty books a year. But when life hit a hefty bump in the road (which is to say, when I was divorced), it dropped considerably. Maybe two or three books a year. I still read a lot for work, because I had to, but pleasure reading took a dive. Today my reading has gone up, but a lot of it is histories and journals and novels about El Salvador during their civil war, because that is what I am also writing about. Some of that is still quite pleasurable. For example, right now I’m reading Sandra Benitez’ The Weight of All Things, which is a beautifully written story of a young boy traveling across the country trying to find his mother after they became separated in a brutal shooting and panic in the capital city. I commend it to anyone.

13. What do you deem the most relevant about your writing? What is the most important to be remembered by readers?

What I hope is the case is that my characters are real and that they speak to our common humanity. They struggle to make sense out of a life that is in chaos and mystery and sometimes make it and sometimes don’t. I strive for their voice to be real and not affected. I want their lives to describe and explain, and hopefully heal, the rifts and tears in our shared aspirations and realities. That’s a little loose and vague, but it’s as close as I can come to touching the deep philosophical, theological heart of my stories. Even my new book, that has the structure of an adventure novel, has a lead character who moves to a developing country to find himself. He has been broken in despair because his wife died suddenly and he blames himself and he hopes that this over-the-top “mid-life crisis” will help heal him and give him the sense of something close to forgiveness. That is the real heart of the story, not whether or not he solves the mysterious crimes of assassinations.

14. What is your opinion about the publishing industry today and about the ways authors can best fit into the new trends?

I’m sure I’m not the first person who has looked at a question like that and something along the lines of, “If I knew the answer to that, I would be a wealthy person.”

The publishing industry is on the ropes right now, just like journalism, churches and brick and mortar stores. The internal fracturing of our society and norms and minds has been going on for decades and there is nothing in the foreseeable future that appears to be an antidote for that. What we might be able to say (perhaps based more on faith than evidence) is that Something will eventually emerge as a new way for writers and life to go on, and a new generation will probably evolve someday that will think of it as the “new normal,” and they will find joy and fulfillment in it. But between our time and that one there will be a great wall of immense pain and loss and dislocation, and there is nothing we can do about it but grieve and breathe and go forward.

My sense is that the best way that authors can be a part of the new “trends” is to chronicle the explosive emotional turmoil ahead of us in a way that readers will be drawn into it and reconciled by it. When readers see themselves and their emotional feelings in literary writing, they learn more about who they are inside and feel (slightly) stronger and more self-aware. The new writing doesn’t have to be straight journalism or history or political punditry, but it does have to have a heartbeat, it has to embody human hurts and aches, and resiliency and resurrections. Writers at their best can help us learn what our insides mean and how to maintain hope and sanity in the midst of a world that has lost its grasp on both.

Second Sunday of Easter, Year A,B,C

Murders and Killings and Who Gets Charged with the Crime

Lent 3 C,

Year C

Luke

13:1-9

13 1At that very time[1]

there were some present who told him about the Galileans whose blood Pilate had

mingled with their sacrifices.[2]

2 He asked them, “Do you think that because these Galileans suffered[3]

in this way they were worse sinners[4]

than all other Galileans?[5]

13 1At that very time[1]

there were some present who told him about the Galileans whose blood Pilate had

mingled with their sacrifices.[2]

2 He asked them, “Do you think that because these Galileans suffered[3]

in this way they were worse sinners[4]

than all other Galileans?[5]

The

Parable of the Barren Fig Tree

|

| Traditional location of the "Pool of Siloam" |

One thing that might be helpful is to point out that, while the literal meaning of the word "perish" (apóllymi), refers to dying or eternal punishment, in the New Testament it is also often used to mean something closer to being lost or estranged or separated. For example, Mark 8:35: "those who want to save their life will lose (apolesei) it, and those who lose their life for my sake, and for the sake of the gospel, will save it." Or the three parables of Jesus in Luke 15, the shepherd who lost a sheep, the woman who lost a coin, and the father who lost his son, all use the word, apóllymi for the thing that is lost, and clearly none of the stories are about someone who is being punished for eternity for their sins.[17]

A more nuanced (and more accurate) reading of Jesus' words here about how we should respond to the deaths of the workers and protesters is to separate the two clauses. On the one hand, no, those people did not die for their sins. And on the other hand, you should not die separated from God. They are not closely related thoughts. You should turn your life around in meaningful, God-related, way now, because you may die estranged, alienated, separated from the love of God and others and yourself.

[17] Gerhard Kittel, Gerhard Friedrich, and Geoffrey William Bromiley, Theological Dictionary of the New Testament (Grand Rapids, MI: W.B. Eerdmans, 1985), p. 67.