Pentecost, Proper 13, Year A

Genesis 32:22-31

His story is about someone who is blessed by God (however deceitfully, it is acquired), but he doesn’t act like it. He spends his entire life (until now) stealing strength from others because he does not have any of his own. He doesn’t act like someone who has the blessing. He acts unblessed. He acts isolated, alienated, abandoned.

Jacob has lived a life of

running away from God and in search of a physical manifestation of the

blessing. He has searched everywhere in all the wrong places. He has mainly

tried to steal it. But all along it has been there already (my words). In this

passage, “he seeks God’s blessing as a way out of the false reality which had

brought him to the point of direct confrontation with his brother.”[1]

“Jacob gives the impression

that throughout his life he considered the search for blessing as his raison d’etre. He does everything he can

in order to get the blessing here at the ford of the Jabbok.[2]

Notice that Jacob at the water’s

edge is trying to avoid getting killed, but not by attacking Esau himself. He

is terrified that Esau still wants to attack him, but he makes no move to

counter the attack. Instead, he sends gifts. What a concept.

Specifically, he does three things:

(1) He divides his wealth into two halves so that if he loses the battle with

his brother, he’ll still have something left. (2) He sends his wives and

children as ambassadors to soften Esau up. (3) And he sends gifts. Big gifts, geese,

pigs, goats, cows, Camels, and more. He separates them into “droves” and has

one servant lead each “drove,” and each when they arrive in front of Esau, they

will bow and scrape and say, “They belong to your servant Jacob; they are a

present sent to my lord Esau; and moreover he is behind us” (Ge 32:18).

“Jacob wishes to shun death, which is lurking in his brother’s four

hundred men, but not by inflicting death himself. His reaction is definitely

not that advised in the often-quoted words of Vegetius: “if you want peace,

prepare for war.” Jacob seeks God’s blessing, which implies the giving of life.

No longer does he rely on his own wits and resources. For that reason he prays

at the ford of the Jabbok with the longest prayer in Genesis, thus finally becoming,

and deserving to be, the patriarch and father of his people, whom he leads to

participation in the blessing of life.”[3]

Let’s set up a background for the story. Jacob, as you recall, had stolen

the family birthright from Esau and had to leave town over it More precisely,

Esau hated his brother and threatened to kill him, precipitating Jacob’s

decision). He landed in a country called Haran ,

where he fell in love with a woman named Rachel (who turns out to be his

cousin, but that’s another story). He arranges to purchase her from her father

Laban for seven years of labor. In the end, the less-than-noble father tricks

him into buying both daughters and working for him 14 years (Tip: don’t read

this story to someone who believes in going back to traditional, biblical

marriage.) In the end he out scams uncle Laban and takes all of his sheep and

goats, and collection of family gods and decides it’s probably time to leave

town again. (They actually forge something of a peace compact at the end, but

by then Jacob is already on the road.)

Now that he is wealthy, middle aged, and weighted down with animals,

servants, wives, concubines and the rage of a father-in-law, he decides (or

receives a message from God [32:9]) that he should finally go back home. However,

one of the things that are “back home” is his brother with whom he has not always

enjoyed cordial relations. When he gets to the border of his brother’s

property, which happened to be a river named the “Jabbok”[4] (probably

a play on the name “Jacob”), he stalls. He is at the dividing line between his

past and his future, and he gets scared. He prays, “Deliver me, please, from

the hand of my brother, from the hand of Esau, for I am afraid of him.” It goes

on and is the longest continuous prayer in the book of Genesis and one of the

longest in the OT. He sends a little welcome gift to Esau, consisting of

(roughly) four hundred goats, two hundred ewes, twenty rams, thirty camels and

colts, and fifty donkeys, thinking, “I may appease him with the present and… perhaps

he will accept me.” Pure bribery. He sends four batches of these gifts.

He’s still not ready to cross the river and the sun is going down, so he

sends the wives, slaves, animals and concubines on over to the other side,

probably hoping that Esau will not kill women and children. But when the time

comes for him to join them, he decides he’d like to stay here for one night

longer to think things over.

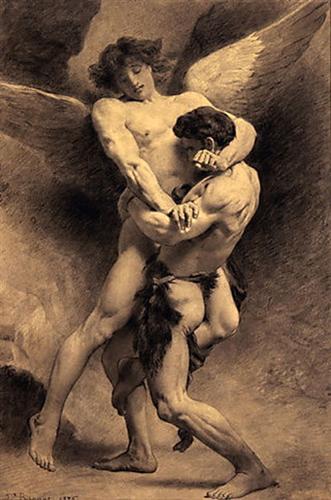

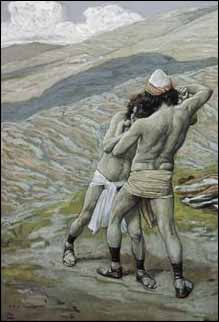

That’s when the wrestling begins. Someone, described solely as “a man” or

“a mortal,” wrestles with him all through the night and into the morning.

Finally, “the man” sees that he can’t get the best of him, so he throws Jacob’s

hip out of joint (limping was an ancient metaphor for when one gains maturity

and wisdom). Jacob demands and receives an honest (as opposed to stolen) blessing,

but interestingly, he is not allowed to receive the blessing until he gives up

his own true name. When he admits his name-- “Jacob, the one who grasps people

by the heel”-- he admits who he truly is, his true character. And when he does

that, he is finally able to be blessed. It is finally a real blessing, not a

heisted one. With the blessing also comes a new name, “Israel,” which means fairly

literally, “the one who has duked it out with God and humans and lived to tell

about it.” The man leaves and Jacob crosses the river, though now he walks with

a limp. He’s a little older, a little wiser, and perhaps for the first time

ready to take on the mantle of the patriarch of this great family.

Once when I preached on this story, I said that even today there is a slight

tendency among many of us to believe that when someone walks with a slight

limp, and perhaps has a cane, that indicates both age and wisdom. Old people

are more inclined to limp, and old people are more inclined to have the wisdom

of age. So, to illustrate the meaning behind the metaphor, I (with some advance

notice) looked out into the crowd and picked on some beloved parishioner who is

of advanced age, and who had a limp and a cane and said something like, “See?

Look, for example at [her name] out there with her cane, she’s the smartest

person in the room. If she wasn’t around, who would I go to for advice on taking

care of myself and getting proper rest? And if you don’t think she’s wise, she

will beat you with that cane.” (A little snarky at the end, but it gave me a

chance to make the illustration and honor one of our grandest parishioners at

the same time.)

Who is the man with whom he wrestles? Theories have abounded for

centuries. They include a Bedouin thief who stumbles upon him and tries to rob

him, a mythic encounter with a river demon (they had a face of a wolf and a

body of a human and they would crawl out of the water late at night and eat the

campers), and (enticingly) Esau, who might have snuck over the river early to

have it out with his brother alone in advance of the official meeting the next

day. This lends itself to many of you who know a story of two family members

who reconciled their differences in some secret struggling way.

I once told the story in a sermon of a parishioner of mine whose father

died, but he had not seen his brother in twenty years and didn’t know how to

inform him of the funeral (and not sure the brother would want to come). The brother

had left the family in an angry huff, decades ago, and never looked back and now,

no one even knew where he was. So, after doing a little Google searching, we

finally ran across him down in Connecticut. My parishioner wrote him a note

about the service coming up and got a surprising email back saying that he

would be coming in on Friday, and just for the service.

However, what really happened is that he came in on Thursday unannounced,

and took his brother, my parishioner out for coffee. And there they sat for

four hours, going through ancient grievances, rehashing old wounds, sometimes

angrily, sometimes passionately. And at the end of the evening, they hugged and

(in their own way) “blessed” each other and the brother left. He went away and

then arrived “officially” the next day for the funeral and he has kept in touch

ever since. I’m sure there are many stories like that one that you can share if

you raise, or go in the direction of, the theory that the person at the river’s

edge was in fact Esau.

However, I don’t think that that was what happened. I think that no

matter who was his actual, historical, physical wrestling partner that night,

in the dark reaches of his soul, Jacob was really wrestling with Jacob. He was

wrestling with his conscience, with his fears, with his resolve. In the

original Hebrew of the conversation between Jacob and his adversary, there is a

blurring of who is speaking in the conversation (“Then he said…” But he said…”

“So, he said…” “and he said…”). It’s hard to follow because it’s hard to understand

who is talking. And that may be on purpose. It’s as if all the characters in

the conversation are the same “he.”

And when one wrestles with oneself, one is inevitably and invariably also

wrestling with God. His new name (Israel , “the one who wrestles with

God”) and the name he creates for the wrestling match (Peniel, “the face of

God”), indicate that at bottom, it was with God that he wrestled. But God does

not wrestle for no purpose and that’s why I think the issue of the wrestling

was his conscience, guilt, and fears.

He knew what he needed to do. He knew where he needed to go. He knew who

he needed to see. It was right and it was moral and it was just for him to

finally return home and to finally reconcile with his estranged brother with

whom he had destroyed community so many years earlier.

But he was afraid. All night long he wrestled with who he is and what he

had done and how he could get through with all of this without getting killed.

Finally, at daybreak, he reconciles himself with his past and his God and is

able to move on.

It seems to me that we could apply this story both communally and

individually. Communally, one could say that it relates to all of you church

people out there. We are at a River Jabbok moment in our history. We have taken

an historic hit in the last couple of generations, in terms of loss of members

and funds and we may not make it into the next one. We have a spotty past and

an uncertain future. This might be a spot in a sermon to talk about courage for

the future.

Individually, we could

apply it just as easily at our own selves. How many of us know where we need to

be but are terrified at getting there? How many of us attempt to buy off our

enemies, send our “wives” on up ahead, but prefer to wait back behind until the

time is just right? I used to know a brilliant linguist who thought he had

invented the world’s most perfect shorthand system. It would revolutionize

note taking. It would make him a fortune. He even asked me if I would head up

the nonprofit foundation he would establish with the proceeds when he made his

millions. But he sat on it for decades, not quite being ready to launch the

product for fear that the public might not be as excited about it as he

believed they should be. In the end computers came in with voice actualization

stenography, and he was ruined. He never made his way across the river.

[1]

[2] Ibid.

[3] Ibid., p. 509

[4] “Jabbok” (yabbôq). “Emptying.” It’s a Transjordanian river that runs from modern Amman, Jordan, north and west into the Jordan.

Detailed exegetical and background notes on the passage:

Genesis 32:22-31

Jacob[1]

Wrestles with who Knows What, at Peniel

The same night he got up and took his two wives, his two maids, and his

eleven children, and crossed the ford of the Jabbok.[2] 23 He

took them and sent them across the stream, and likewise everything that he had.

24Jacob was left alone;[3] and a man[4] wrestled

with him until daybreak. 25 When the man saw that he did not prevail

against Jacob, he struck him on the hip socket; and Jacob’s hip was put out of

joint[5] as he

wrestled with him.

26 Then he said, “Let me

go, for the day is breaking.”

But Jacob said, “I will not let you go, unless you bless[6] me.”

27 So he said to him, “What

is your name?”

And he said, “Jacob.”[7]

28 Then the man[8] said, “You

shall no longer be called Jacob, but Israel ,[9] for you

have striven[10]

with God and with humans,[11] and have

prevailed.”

29 Then Jacob asked him,

“Please tell me your name.”

But he said, “Why is it that you ask my name?” And there he blessed him.[12]

30 So Jacob called the place Peniel,[13] saying, “For

I have seen God face to face, and yet my life is preserved.” 31 The

sun rose upon him as he passed Penuel, limping because of his hip.[14] 32 Therefore

to this day the Israelites do not eat the thigh muscle[15] that is

on the hip socket, because he struck Jacob on the hip socket at the thigh

muscle.

ENDNOTES and COMMENTARY

[1] In light of Jacob’s history and what is to come, it is

interesting to note that his name, “Jacob” is derived from ‘aqab, to seize by the heel; fig. to circumvent (as if tripping up

the heels); also to restrain (as if holding by the heel)—take by the heel,

stay, supplant. He got his name by holding onto the heel of his older twin

brother during birth and forcing the brother to pull them both out of their

mother’s womb. He has remained a grabber, or a rider on someone else’s heel all

the rest of his life.

[2] “Jabbok” (yabbôq). “Emptying.” A

Transjordanian river from modern Amman, Jordan, north and west into the Jordan.

[3] Notice that Jacob had sent over all of his animals and

servants (in the passage just previous to this) and then his wives and

concubines (in this passage) but he doesn’t join them. Is he thinking he needs

his rest? Did the night fall too quickly for him to go with them? Or was he

simply terrified of meeting his brother on the other side of the river who has

announced that he has four hundred troops with him to greet Jacob with.

[4] “Man” (אישׁ ‘îysh). Not the generic ‘âdâm,

“mortal” or “humanity,” but specifically “man.” The female counterpart would be

‘îyshά. The most common theory as to with whom he was

wrestling is God (implied in 32:28, 30) or an angel (Hos. 12:4), but there are

others. They include, a Bedouin thief who stumbled upon Jacob and tried to rob him,

a mythic night demon (who had to be gone by daylight), and (enticingly) Esau

who snuck over the river early to have it out with his brother alone in advance

of the official meeting the next day or Jacob wrestling with himself. Jacob’s

new name (Israel, “the one who wrestles with God”) and Jacob’s name for the

location (Peniel, “the face of God”) argue for its being God, nd it’s clear,

even if it was Esau or himself, in the end God is at least within the other with whom Jacob is wrestling. The Inclusive Language Torah (Priests for Equality, Hyattsville,

Maryland) suggests Esau. It notes that “the Hebrew in the…passage is almost

completely lacking in proper names—each line of dialogue begins, ‘And he said,’

without any indication of who is speaking, a dizzying construction which gives

the reader the idea that Jacob and the Other are mirror images of one another –

Jacob in effect wrestling with himself, or figuratively wrestling with his

twin, Esau, whom he is about to confront.” It is interesting to note that in

the next chapter, v. 10, when Jacob finally meets Esau, he says, “Seeing you is

like seeing the face of God.”

[5] Walking with a limp was a sign that one had moved into an

age of humility and maturity. Often a metaphor for wisdom. See v. 31.

[7] “Jacob” (יעקב ya‛ăqôb). From עקב ‛âqab heel catcher or supplanter. As used here to apply to

Jacob, it means something more like, “the one who gets along in life by pulling

at someone else,” Or more bitingly, “one who uses others to get by.” Giving his

name to the mysterious man means admitting who he is. This is the first time he

has done this in the Jacob saga.

[9] “Israel.” Associated with the rare verb śārâh,

‘struggle’ plus el the Canaanite name

for deity. The combination can produce two meanings: the One who struggles with God (and survives), or God who strives or struggles. The consensus

preference is probably the former. The NET, however, prefers the latter and

believes it should read, “God fights.” They say, “In essence, the LORD was saying that Jacob would have victory

and receive the promises because God would fight for him.”

[10] “Striven” (śārāh). Verb. To persist, contend, persevere.

The word is used figuratively in Hosea, 12:4-5.

[11] Or with divine and

human beings

[12] To have someone’s name is to have power over the person.

God would not (yet) let that happen. That was left for Moses, many generations

later. On the other hand, to change

someone’s name was seen as having authority over the other person. The IVP Bible

Background Commentary notes that “When a suzerain put a vassal on the

throne, he sometimes gave him a new name, demonstrating his power over that

vassal.” (Victor Harold Matthews, Mark W. Chavalas and John H. Walton, The IVP Bible Background Commentary: Old

Testament, [Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 2000]).

[13] That is The face of

God

[14]

“Limping because of his hip.” To say that someone “limped” was a common

metaphor in ancient Israel for one who has come into maturity and is considered

wise.

[15] “Israelites do not eat

the thigh muscle…” That Israelites are not to eat the sinew of the hip or the

sciatic nerve of any animal because this part of the body was touched by the

[divine] hand of the one who wrestled Jacob (v. 32) is not otherwise known in

Israelite law.