Hold Fast to the Dream

A

Presentation for Two Readers and Choir

Acknowledgements

The author gratefully acknowledges the help and advice of Joe Bradley,

Tinker Monroe, Laura Delaplain, Erma LaPierre, René LaPierre, and Beverly Latif

Duncan for their work in either presenting or critiquing earlier drafts of this

manuscript, and the adult choirs of the Congregational Church of South Hadley

Falls and the United Church of Christ in Abington, Massachusetts for their

roles in its first performances.

Introductory Notes

“Hold Fast to

the Dream” was first written for a Sunday morning service of worship, perhaps

taking the place of the Sermon. Later it was expanded to make it adaptable for

a longer presentation of the type that might be used as an afternoon or evening

event in which the music and readings comprised the entire program. For

example, the Sunday of the Week of Prayer for Christian Unity is often the same

Sunday as Martin Luther King Sunday, and would be a good occasion for a

presentation such as this. The expanded portions are set off by double lines.

When doing the short form, simply skip those sections. In the expanded form,

add them.

A word on

music. Many of the hymns suggested in “Hold Fast to the Dream” can be found in

various hymnals and other collections. Most are in public domain and will be

free. One fine collection that contains all of the music here is Sing for Freedom: The Story of the Civil

Rights Movement Through its Songs, by Guy and Candie Carawan (Bethlehem,

PA: Sing Out Corporation, 1990). However, before using music from this or any

other collection in a public presentation of “Hold Fast to the Dream,” you

should first contact the publishers for permission. Normally there will be

little difficulty gaining permission to use their work. But, if for some reason

you are unable to attain the music or apply for permission, the song, “We Shall

Over Come” can be nicely substituted throughout with little loss to the overall

program. In this text, both “We Shall Over Come” and a second option (which can

be found in Sing for Freedom and

other collections) are always given whenever a piece of music is suggested.

Note that

preceding each of the readings, there is a heading which usually contains a

title, date, and place of its delivery. For most of the readings, these

headings are for the benefit of the readers only. The context usually

introduces the reading adequately. One exception is the excerpt from the proclamation

for Martin Luther King day at the end. This is not introduced in the text and will be confusing without the title

given. However, the titles can also be useful if a particular reading is taken

out of this presentation and used separately in another occasion as a smaller

individual reading.

It should also

be noted that the proclamation at the very end has troubled some people who

have participated in this presentation. The president who said these words was

Ronald Reagan, who frequently opposed King's work philosophically and also

opposed the founding of “Martin Luther King Day,” for which these words were

written. Some, therefore, have felt it hypocritical to use his words to honor

Rev. King. To be sensitive to that criticism, here are three options. First, in

this version we have introduced the proclamation by saying (truthfully) that

these words were written, not by the

president, but for him to read (by

speech writer Peggy Noonan), and the name of the president is not mentioned. A

second option is to simply end with the last words of King to Abernathy as he

lay dying. The dramatic conclusion is a good ending by itself. Finally, if anyone

in your troupe is creative, feel free to write a conclusion of your own with

our blessing.

Early Years

NARRATOR:

On one very

cold and very cloudy Saturday morning, January 15, 1929 , just three months after the beginning of

the worst economic depression in the history of the United States

They named him

Martin, after his father, and he would grow up to make it one of the most

famous names in all of American history. Little Martin Luther King Jr. would,

in his lifetime, change the way people understood democracy, religion, race

relations, and human relations, throughout the entire world.

Young Martin

grew up in a relatively middle class home but in a very segregated Atlanta , Georgia America

He could not buy a Coke or a

hamburger at any of the downtown stores. He could not sit at a lunch counter.

He could not drink water at the “whites only” water fountains, he could not use

the “whites only” restrooms, and he could not ride on the “whites only”

elevators. If he went to a theater he would have to enter from the “colored”

entrance. If he rode a bus he would have to sit in the back, in the “colored”

seats, and if he wanted to go swimming, golfing, or play tennis, he simply

couldn’t because all of the pools, courses, or courts had “whites only” signs

in front of them.

Here are some

of his own reflections on what it was like to grow up in a segregated world.

KING: (“Growing Up Negro”)

[Growing up] a

Negro in America America America

CHOIR: “We Shall

Overcome,” verse 1

We shall

overcome,

we shall overcome,

we shall overcome some day.

Oh, deep in my

heart,

I do believe,

that we shall overcome some day.

NARRATOR: [Music over, melody only, of “We Shall

Overcome”]

When he graduated from high school, he went on to Morehouse College

in Atlanta , then Crozier Seminary in Pennsylvania

In later years

it was discovered that King copied several quotations from another dissertation

into his own without citing them correctly. The act was unfortunate because it

has allowed critics to unfairly smear his intelligence in spite of his obvious

brilliance.

In Boston he

met a young woman named Coretta Christine Scott, who was a graduate student at

the New England Conservatory of Music. At first he was unsure about her because

he’d heard that she wasn’t too religious; and she was unsure about him because

she had heard that he was too short. But after they got to know one another, he

grew to believe that her faith was not showy but deeper on the inside than

anyone’s he ever knew. As for her concerns, he never grew any taller on the

outside, but on the inside he became a giant.

the New England Conservatory of Music. At first he was unsure about her because

he’d heard that she wasn’t too religious; and she was unsure about him because

she had heard that he was too short. But after they got to know one another, he

grew to believe that her faith was not showy but deeper on the inside than

anyone’s he ever knew. As for her concerns, he never grew any taller on the

outside, but on the inside he became a giant.

the New England Conservatory of Music. At first he was unsure about her because

he’d heard that she wasn’t too religious; and she was unsure about him because

she had heard that he was too short. But after they got to know one another, he

grew to believe that her faith was not showy but deeper on the inside than

anyone’s he ever knew. As for her concerns, he never grew any taller on the

outside, but on the inside he became a giant.

the New England Conservatory of Music. At first he was unsure about her because

he’d heard that she wasn’t too religious; and she was unsure about him because

she had heard that he was too short. But after they got to know one another, he

grew to believe that her faith was not showy but deeper on the inside than

anyone’s he ever knew. As for her concerns, he never grew any taller on the

outside, but on the inside he became a giant.

And on June 18, 1953 they were

married.

MONTGOMERY

NARRATOR:

Six months

later, in January of 1954, King was invited to come to Montgomery ,

Alabama , to interview for pastor of the Dexter Avenue

Baptist Church

November 17,

after Martin and Coretta had arrived and begun to get settled in with their

church and new home, their first child, Yolanda, was born.

And on December

1, as he was making plans for a series of sermons on the coming of the Christ

Child at Christmas, a black seamstress in Montgomery

Blacks were

wanting to riot and whites were wanting to kill blacks who were wanting to

riot. So, the black community elected young father, young preacher, young

seminary graduate Martin Luther King to organize them to respond to the crisis.

Over two

thousand people rallied in front of a church that night to decide what they

would do. The air was tense and explosive. It was a dangerous night for both

blacks and whites. Rev. Martin Luther King stood up to speak to them that night

and here are some of the words that he said. [music stops]

KING: (Montgomery

(December 5,

1955, at the Holt St. Baptist Church, Montgomery, Alabama)

We are here

this evening for serious business. We’re here in a general sense because first

and foremost, we are American citizens, and we are determined to acquire our

citizenship to the fullness of its meaning. We are here also because of our

deep-seated belief that democracy transformed from thin paper to thick action

is the greatest form of government on earth.

But we are here in a specific

sense because of the bus situation in Montgomery United States

But in our protests, there will be no cross

burnings. No white person will be taken from his home by a hooded Negro mob and

brutally murdered. There will be no threats and intimidation. We will be guided

by the highest principles of law and order...the deepest principles of our

Christian faith. Love must be our regulating ideal....If we fail to do this our

protest will end up as a meaningless drama on the stage of history, and its

memory will be shrouded with the ugly garments of shame. In spite of the

mistreatment that we have confronted, we must not become bitter and end up by

hating our white brothers. Let no people pull you down so low as to make you

hate them.[2]

NARRATOR:

[Music over]

So, instead of

a riot, they organized a boycott of the Montgomery buses, with car pools taking

people to work. Non violently they brought the city to its knees. The city took

them to court arguing for segregation all the way to the Supreme Court.

Finally, after over a year of attacks and threats and thousands of daily hate

letters and phone calls, after his home was bombed and the police refused to

investigate, and after King himself was arrested and jailed twice for speeding

and had to pay hundreds of dollars in fines and had his auto insurance policy

revoked, after the movement had to spend tens of thousands of dollars in legal

fees and bail, after all of this and more, the Supreme Court declared that

segregation of public transportation facilities was unconstitutional.

CHOIR: “We Shall

Overcome” verse 2.

We’ll go hand in

hand,

We’ll go hand in hand,

We’ll go hand in hand, some day.

Oh, deep in my

heart,

I do believe,

that we shall overcome some day.

Or: “If You Miss

Me From the Back of the Bus.”

If you miss me

at the back of the Bus,

and you can’t find me nowhere,

Come on up to the front of the bus,

I’ll be riding

up there,

I’ll be riding up there,

I’ll be riding up there.

Come on up to the front of the bus.

I’ll be riding up there.

SIT-INS

[Music over]

King and his

movement became internationally famous after that. Together with Ralph Abernathy

and others, they founded the Southern Christian Leadership Conference and began

organizing voter registration throughout the South. At that time, less than ten

percent of blacks in America

In 1960 four

black college students in Greensboro

North Carolina

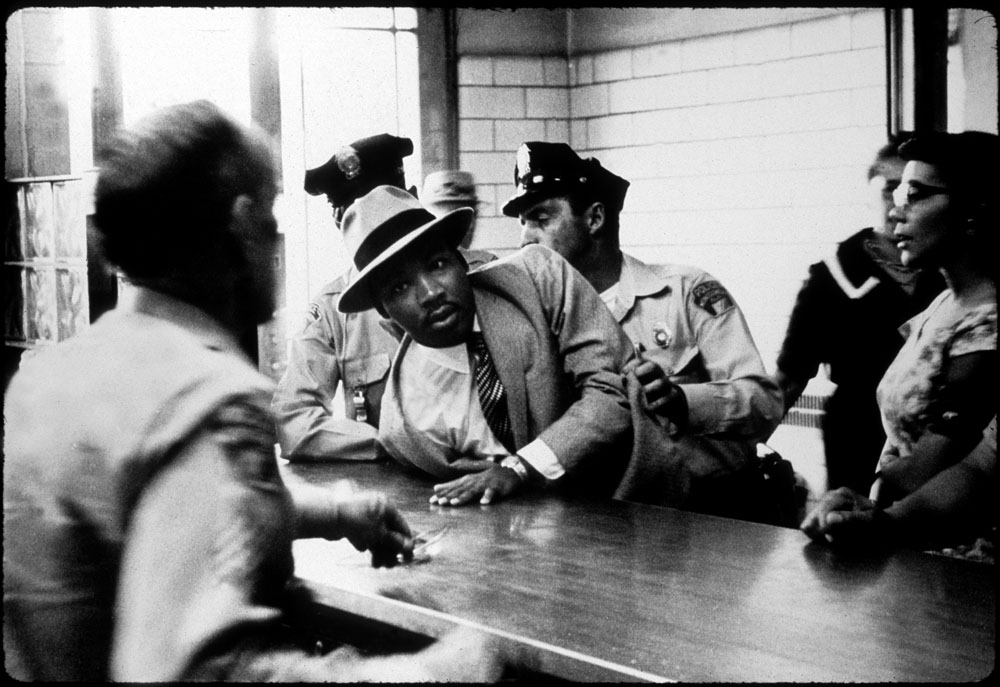

In October of

that year, Rev. King and several others joined a “sit-in” in Atlanta , Georgia

While in

prison, wearing leg irons, eating rancid food, in an unheated room, infested

with bugs, Martin wrote this letter to his wife, Coretta:

[music stops]

KING: (Letter

to Coretta)

(October 26, 1960, in Georgia’s maximum

security prison for a traffic violation after being arrested at a sit-in in

Atlanta, Georgia.)

Hello Darling,

Today I find

myself a long way from you and the children...I know this whole experience is

very difficult for you to adjust to, especially in your condition of pregnancy,

but as I said to you yesterday this is the cross that we must bear for the

freedom of our people....

I have the

faith to believe that this excessive suffering that is now coming to our family

will in some little way serve to make Atlanta a better city, Georgia a better

state, and America a better country.

Just how, I do

not know yet, but I have faith to believe it will. If I am correct then our

suffering is not in vain.

I understand

that everybody—white and colored—can have visitors this coming Sunday. I hope

you can find some way to come down....

Give my best

regards to all the family. Please ask them not to worry about me. I will adjust

to whatever comes in terms of pain. Hope to see you Sunday.

Eternally

yours,

NARRATOR:

[Music over]

But King did

not spend the four months in prison. As it happened, a young U.S.

CONGREGATION AND

CHOIR: “Amen, Amen”

Or:

CHOIR: “We Shall

Overcome” verse 3,

We are not

afraid

We are not afraid

We are not afraid, some day.

Oh, deep in my

heart,

I do believe,

that we shall overcome some day.

Or:

“Keep Your Eyes

on the Prize” verses 1,2.

Paul and Silas

bound in Jail

Had no money for to pay their bail

Keep your eyes on the prize, Hold on.

Hold on.

Hold on.

Keep your eyes on the prize,

Hold on.

Paul and Silas began to shout,

the jail door opened and they

walked out.

Keep your eyes on the prize, hold

on....

BIRMINGHAM

NARRATOR:

[music over]

The reputation

of Martin Luther King and the movement grew larger and larger through the early

sixties. There were more sit-ins, there were more boycotts, there were more

protests, all slowly tearing down the most visible excesses of the walls of

oppression and discrimination in America

But perhaps the

turning point in his life, and the life of the movement, took place in 1963 in Birmingham , Alabama

The police

commissioner of Birmingham Birmingham

On April 3, 1963 , the protest

of Birmingham

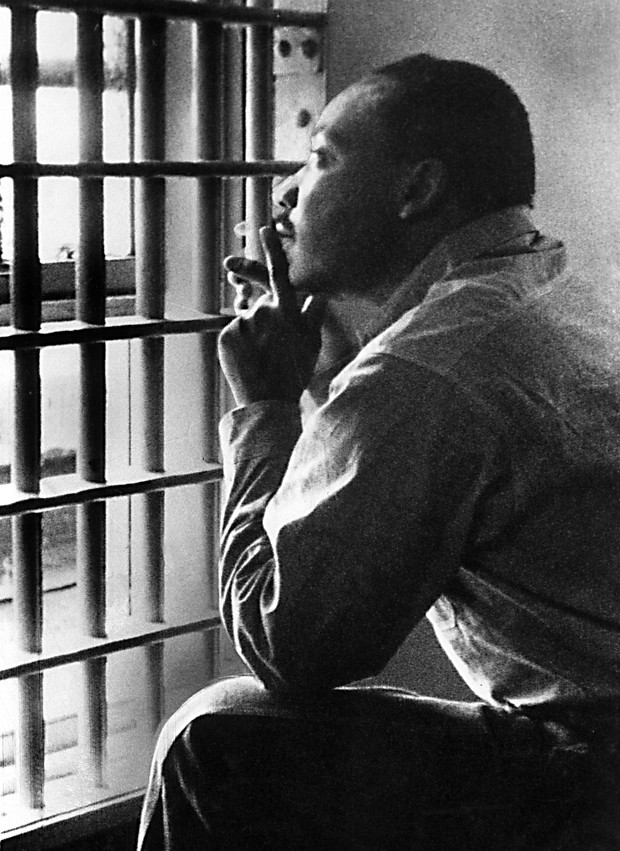

While there, he

had been given a newspaper in which a number of white clergy, Christian and

Jewish, had written a public letter criticizing him for pushing integration too

quickly. He sat down in his cell and on pieces of newspaper, rags, toilet

tissue, and backs of envelopes, he wrote a public response. His response became

known as the “Letter from Birmingham Jail,” and has become one of the most

famous statements about non- violent civil disobedience written in this

century. And here is a portion of what he said.

[music ends]

KING: (“Letter

from Birmingham

(April 16, 1963 , while imprisoned in the Birmingham City

My Dear Fellow

Clergymen:

While confined here in Birmingham

[You are right

when you note that we are outsiders coming in to your community, but we have

come to Birmingham Atlanta and not be concerned about what happens in Birmingham United States

[You also mentioned the demonstrations in Birmingham

[You told us

that our protests were “untimely” and that we should trust you and “wait.” For

centuries the Negro has heard “wait,” and “wait” has nearly always meant “Never.”] We have waited for more than 340 years for

our constitutional and God-given rights...Perhaps it is easy for those who have

never felt the stinging darts of segregation to say, “wait.” But when you have

seen vicious mobs lynch your mothers and fathers at will, and drown your

sisters and brothers at whim; when you have seen hate-filled policemen curse,

kick and even kill your black brothers and sisters; when you see the vast

majority of your twenty million Negro brothers [and sisters] smothering in an

airtight cage of poverty in the midst of an affluent society; when you suddenly

find your tongue twisted and your speech stammering as you seek to explain to

your six-year-old daughter why she can’t go to the public amusement park that

has just been advertised on television;...when you have to concoct an answer

for a five-year-old son who is asking: “Daddy, why do white people treat

colored people so mean?; when you take a cross-country drive and find it

necessary to sleep night after night in the uncomfortable corners of your

automobile because no motel will accept you; when you are humiliated day in and

day out by nagging signs reading “white” and “colored”; when your first name

becomes “nigger,” your middle name becomes “boy” (however old you are)...; and

your wife and mother are never given the respected title of “Mrs.”; when you

are harried by day and haunted by night by the fact that you are a Negro,

living constantly at tiptoe stance, never quite knowing what to expect next,

and are plagued with inner fears and outer resentments; when you are forever

fighting a degenerating sense of “nobodiness”—then you will understand why we

find it difficult to wait.[4]

NARRATOR:

[Music over]

Outside, “Bull”

Connor seemed intent on proving that racism could be even more evil than King

had described it in his letter. He had firemen turn fire hoses on the marchers,

which sent columns of water crashing into children and adults, knocking them

down, ripping their clothing, smashing them against the sides of buildings,

sweeping them off of the streets, bloodying their bodies and throwing them into

parks and alleys. Then he let loose German shepherd dogs trained to attack and

bite and tear at running people. Day after day television cameras showed a

shocked world the horrors, but day after day the carnage continued, and day

after day the marchers continued marching for freedom.

The turning

point occurred on Sunday, May

5, 1963 , when three thousand children went on a prayer vigil to the

Birmingham

“Bull” Connor

yelled at his men to turn on the hoses, but nobody moved. The children continued

praying. His men were silent. He yelled again, but they dropped their hoses.

One of the firemen began crying. “We can’t continue to do this,” one of them

said. The children continued silently praying. Nobody spoke again, and nobody

got hurt. That event was the moral turning point of the struggle. Soon after

that, the businesses of Birmingham agreed to integrate.

“The Storm is Passing Over”

Or: “We Shall

Overcome,” verse 4.

Our God will see

us through,

Our God will see us through,

Our God will see us through, some day.

Oh, deep in my

heart,

I do believe,

that we shall over come some day.

Or: “Keep your

Eyes on the Prize,” Verses 3, 4, 5.

The only Chain

that we can stand,

is the chain of

hand in hand...

Keep your eyes

on the prize, Hold on.

Hold on.

Hold on.

Keep your eyes

on the prize, Hold on.

The only thing

that we did wrong,

was stay in the

wilderness too long.

Keep your eyes

on the prize, hold on....

The only thing

we did right,

was the day we

started to fight.

Keep your eyes

on the prize, hold on....

WASHINGTON

NARRATOR:

[music-over]

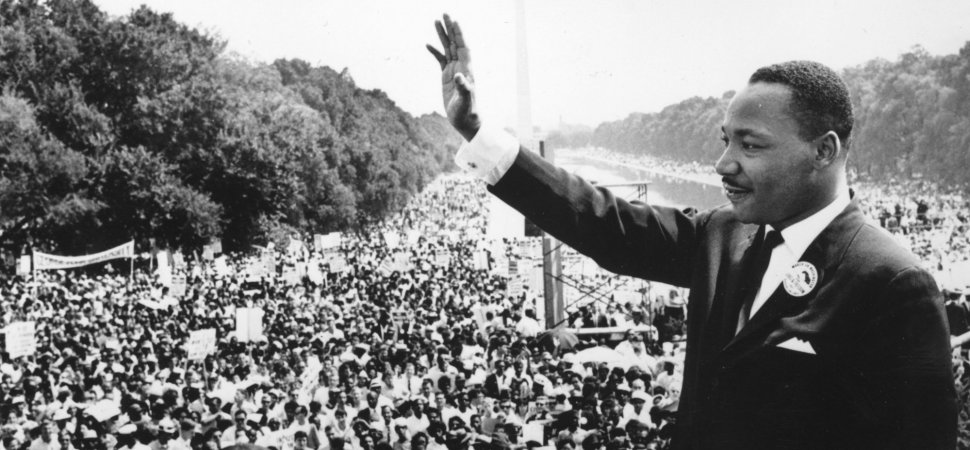

The next few

years were a whirlwind. In the space of just one year the Supreme Court ruled

that segregation in Birmingham Vatican ,

and he led a successful 125,000 person “Walk for Freedom” in Detroit August 28, 1963 , he took part in the largest

civil rights demonstration in history, in Washington

DC

[music ends]

KING: (“I Have

a Dream”)

(August 28, 1963, from the steps of the

Lincoln Memorial, Washington, DC)

...I say to you

today, my friends...even though we face the difficulties of today and tomorrow,

I still have a dream. It is a dream deeply rooted in the American dream.

I have a dream

that one day this nation will rise up and live out the true meaning of its

creed: “We hold these truths to be self-evident; that all men are created equal.”

I have a dream

that one day, on the red hills of Georgia

I have a dream

that one day even the state of Mississippi, a state sweltering with the heat of

injustice, sweltering with the heat of oppression, will be transformed into an

oasis of freedom and justice.

I have a dream that my four little children will one day

live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin but

by the content of their character.

I have a dream today.

I have a dream

that one day, down in Alabama, with its vicious racists, with its governor

having his lips dripping with the words of interposition and nullification, one

day right there in Alabama, little black boys and black girls will be able to

join hands with little white boys and white girls and walk together as sisters

and brothers.

I have a dream today.

I have a dream

that one day “every valley shall be exalted, every hill and mountain shall be

made low, the rough places will be made plains, and the crooked places will be

made straight, and the glory of the Lord shall be revealed, and all flesh shall

see it together.”

This is our

hope. This is the faith that I go back to the South with. With this faith we

will be able to hew out of the mountain of despair a stone of hope. With this

faith we will be able to transform the jangling discords of our nation into a

beautiful symphony of brotherhood. With this faith we will be able to work together,

to pray together, to struggle together, to stand up for freedom together,

knowing that we will be free one day.

And this will be the day. This will be the day when all of

God’s children will be able to sing with new meaning “My country ‘tis of thee, sweet

land of liberty, of thee I sing. Land where my fathers died, land of the

pilgrim’s pride, from every mountainside, let freedom ring.”

And if America New Hampshire New York California

But not only

that; let freedom ring from Stone Mountain Georgia Lookout Mountain Tennessee

Let freedom

ring from every hill and molehill of Mississippi

And when this

happens, and when we allow freedom to ring, when we let it ring from every village

and every hamlet, from every state and every city, we will be able to speed up

that day when all of God’s children, black men and white men, Jews and

Gentiles, Protestants and Catholics, will be able to join hands and sing in the

words of that old Negro spiritual, “Free at last! Free at last! Thank God

almighty, we’re free at last!”[5]

CHOIR: “Free At Last”

Or: “I Want to be Ready”

Or: “We Shall

Overcome,” verse 5.

The truth shall

make us free,

The truth shall make us free,

The truth shall make us free, some day.

Oh, deep in my

heart,

I do believe,

that we shall overcome some day.

MEMPHIS

NARRATOR:

[music over]

Over the next

few years the dream of King seemed to go bad. Protesters who promoted violence

seemed to be on the rise and people who promoted love and peace among all

people seemed to be on the decline. Riots in Watts, Detroit ,

Newark

Increasingly

during this time King was growing to believe that race is only one of the

issues which was at the core of America Washington

But right in

the middle of his plans for the march, he was asked to come to Memphis , Tennessee April 3, 1968 .

[music ends]

KING: (“I’ve Been To The Mountain Top”)

(Last speech, before a rally in support of

the Memphis garbage strike, April 3, 1968 , in Memphis , Tennessee

...We have been

forced to a point where we’re going to have to grapple with the problems that

people have been trying to grapple with through history, but the demands didn’t

force them to do it. Survival forces

us to grapple with them. For years now people have been talking about war and

peace. But now no longer can they just talk about it. It is no longer a choice

between violence and nonviolence in this world, it is nonviolence or nonexistence.

[Begin music

over of “Mine Eyes Have Seen the Glory.”]

That is where

we are today. And also in the human rights revolution, if something isn’t done,

and in a hurry, to bring the colored peoples of the world out of their long

years of poverty, their long years of hurt and neglect, the whole world is

doomed.

...If I lived

in China or even Russia America

...Let us rise up tonight with a greater readiness. Let us

stand with a greater determination. And let us move on in these powerful days,

these days of challenge, to make America

...I don’t know

what will happen now. We’ve got some difficult days ahead. But it really

doesn’t matter with me now, because I’ve been to the mountain top. And I don’t

mind. Like anybody, I would like to live a long life; longevity has its place.

But I’m not concerned about that now. I just want to do God’s will. And God’s

allowed me to go up to the mountain. And I’ve looked over. And I’ve seen the

promised land. I may not get there with you. But I want you to know tonight

that we as a people will get to the promised land. And I’m happy tonight, I’m

not worried about anything. I’m not fearing anyone. Mine eyes have seen the

glory of the coming of the Lord.[6]

NARRATOR:

[No music]

The next day,

The next day,

At about 5:00,

they all began to change clothes and get ready for dinner. They were going to

the home of a local pastor who had invited all of them over for dinner. A few

moments before six, the pastor arrived and people began to gather outside to

leave. King stood at the doorway and yelled in to Abernathy, “Are you ready?”

Abernathy said back, “Let me put on some after shave lotion.” King said, “Ok.

I’ll be standing out here on the balcony.”

At 6:05 that evening, Martin Luther

King, Andrew Young, Jesse Jackson, and several others were standing on the

second floor balcony of the Lorraine Motel in Memphis , Tennessee

At 6:09 they

heard the sound of a shot ringing out. The sound of a .30-06 high-powered

rifle. King slammed backwards against the wall of the balcony and then fell

forward onto the balcony floor. Ralph Abernathy rushed out to him. Someone else

found a pillow to put under his head. A secret service agent held a towel to

the wound in his neck to try and stop the bleeding. Others were running up the

stairs, some were running for cover, some were screaming.

* * *

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

During the next few minutes Ralph held the head of his

dearest, closest friend in his lap while waiting for an ambulance to arrive,

and watching the life bleed out of him. He spoke to Martin several times during

those minutes, but Martin could only respond with his eyes. Years later Ralph

said that he heard much from those eyes that night. Martin Luther King looked

at him very awake, and very alert, and with his eyes he seemed to be speaking

very clearly. He was saying, “Ralph, it isn’t over. It’s only in other people’s

hands now. Don’t give up. Never give up. Never give up. Never give up. Never

give up.” ...And then he died.

PROCLAMATION FOR

MARTIN LUTHER KING JR. DAY, 1986

Written to be read by the President of the United States November 2, 1986 .

Read, or compose your own conclusion using local allusions.

“Let all Americans continue to carry forward the banner

that...fell from Dr. King’s hands. Today, all over America

“Precious Lord, Take My Hand,”

verses 1,2,3.

Precious Lord, take my hand,

lead me on, let me stand,

I am tired, I am weak, I am worn;

Through the storm, through the

night,

lead me on to the light:

Take my hand, precious Lord, lead me

home.

When my way grows drear,

precious Lord, linger near,

when my life is almost gone,

Hear me cry, hear my call,

hold my hand, lest I fall:

Take my hand, precious Lord, lead me

home.

When the shadows appear

and the night draws near,

and the day is past and gone,

At the river I stand,

guide my feet, hold my hand:

Take my hand, precious Lord, lead me

home.

Printable versions of the program:

Here are two links for two different printable versions.First, click here for a small booklet version (set your printer for "booklet," and print on both sides of the paper and to flip on the short end)

However, because systems can vary, the booklet may not print out well for you. If that is the case, a simple, upright, "Portrait," letter-size, version can be found by clicking here.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Ayres,

Alex. The Wisdom of Martin Luther King,

Jr. New York : Meridian

Books, 1993.

Carawan,

Guy and Candie, eds. Sing For Freedom:

The Story of the Civil Rights Movement Through its Songs. Bethlehem , PA

Garrow,

David. “The Intellectual Development of Martin Luther King, Jr.: Influences and

Commentaries,” Union Seminary Quarterly

Review, (Vol. XL, No. 4, 1986).

King,

Coretta Scott, ed. The Words of Martin

Luther King, Jr. New York

Oates,

Stephen B. Let the Trumpet Sound: the Life of Martin Luther King, Jr. New York

[1] Coretta

Scott King, ed., The Words of Martin

Luther King, Jr. (New York: New

Market Press, 1987), p. 31.

[2] Stephen

B. Oates, Let the Trumpet Sound: the Life

of Martin Luther King, Jr. (New York: Harper & Row, 1994), pp. 70, 71;

and David Garrow, “The Intellectual Development of Martin Luther King, Jr.:

Influences and Commentaries,” Union

Seminary Quarterly Review, (Vol. XL, No. 4, 1986), p. 15.

[3] Alex

Ayres, ed., The Wisdom of Martin Luther

King (New York: Meridian Books, 1993), pp. 183, 194. Toward the end of this

letter, King requested that Coretta bring him several books to read while in

prison. They were deleted from the presentation because the names would be

unfamiliar to most audiences. However, if your presentation group feels that

your particular audience would recognize the names and be interested in knowing

them, feel free to return them to the letter. The following is the deleted

portion:

“Please bring the following books to me: Stride Toward Freedom, Paul Tillich’s Systematic Theology Vol. 1 and 2, George

Buttrick’s The Parables of Jesus, E.

Stanley Jones’ Mahatma Gandhi, Horns and

a Halo, a Bible, a Dictionary, and my reference dictionary called Increasing Your Word Power....”

[4] Let the Trumpet Sound, pp. 223-230.

[5] Words of Martin Luther King, pp. 95-97.

[6] Words of Martin Luther King, pp. 93-94.

[7] Wisdom of Martin Luther King, pp. 226,

227.